You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

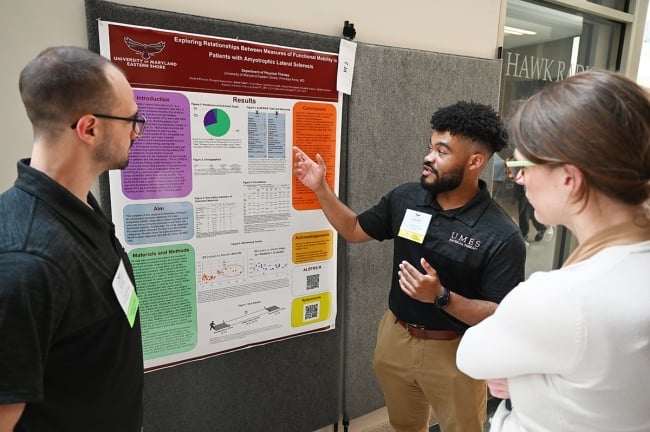

A physical therapy doctoral student at University of Maryland Eastern Shore presents a poster at a graduate research symposium this past spring.

University of Maryland Eastern Shore

The University of Maryland Eastern Shore, a historically Black university, and the University of Maryland Baltimore are contesting a new physical therapy doctoral program proposed by Johns Hopkins University, arguing that it duplicates programs they already offer.

The opposition comes less than a month after Towson University withdrew a proposal for a business analytics doctoral program, opposed by Morgan State University for duplicating one of its programs. Towson leaders argued that the program wasn’t duplicative of the HBCU’s offerings and they plan to resubmit the proposal.

The two conflicts are emblematic of a long, fraught history of conflicts between institutions in the state, particularly HBCUs and once predominantly white institutions, over duplicative academic programs.

Advocates for the state’s four HBCUs—the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, Morgan State, Coppin State University and Bowie State University—sued the state in 2006 for chronically underfunding them and allowing predominantly white institutions to duplicate their programs. Then Maryland governor Larry Hogan signed legislation in 2021 ending the 15-year legal battle and granting $577 million in additional funding to the state’s HBCUs over a 10-year period.

The state Legislature has also undertaken an ongoing examination of the review process of the Maryland Higher Education Commission, which assess proposals for academic programs. The commissioners themselves are eager for guidance and change. But some higher ed experts say the HBCUs’ lawsuit left commissioners with heightened concerns about responding to duplication problems and left Maryland university leaders, especially those at HBCUs wronged in the past, distrustful of one another and quick to object to one another’s programs.

The commission is expected to decide by Thursday whether the Johns Hopkins program can move forward.

A Contested Program

Emily A. A. Dow, the commission’s assistant secretary for academic affairs, said at a hearing earlier this month that the proposed Johns Hopkins program is “duplicative” but not “unreasonably duplicative” of the existing physical therapy doctoral programs and could help meet demand for physical therapists in the state, including within the Johns Hopkins Medical System.

She noted that neighboring states have multiple physical therapy doctoral programs—Pennsylvania has 21 programs, for instance. Cohorts for physical therapy doctoral programs at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore and the University of Maryland Baltimore are capped at 34 and 70 students, respectively, by their accreditor, the Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education. Johns Hopkins is proposing a cohort of 70. Dow further argued that more programs could draw more out-of-state students to Maryland who might stay once they graduate.

“This ultimately can bring new revenue to the state and oftentimes can expand job opportunities as businesses grow,” she said.

Sanjay Rai, the commission’s acting secretary, recommended in July that the program be allowed to proceed. He called on commissioners at the hearing to vote in favor of his decision.

Jill Rosen, a Johns Hopkins spokesperson, said in a statement that Maryland Department of Labor projections suggest the state’s higher education institutions are producing fewer than a third of the state’s estimated annual need for physical therapists.

“Johns Hopkins University is pleased that our program proposal for a Doctorate of Physical Therapy has been recommended for implementation by the Maryland Higher Education Commission (MHEC),” Rosen said. “We maintain our position and concur with MHEC that the proposed DPT program is not unreasonably duplicative of existing programs.”

University of Maryland Eastern Shore and University of Maryland Baltimore administrators argue that the Johns Hopkins program could take prospective students and faculty members away from their programs and take up already scant clinical sites for training.

“This program does cause harm in a number of ways,” Heidi Anderson, president of the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, said at the hearing. “It will cause harm to students, current and future. It will cause harm to patients, current and future. And it would also cause harm to our program.”

Anderson noted that the commission previously prevented Stevenson University from opening a similar program because of the problems it could cause to existing programs. (That decision is currently being revisited by the commission, with a decision due next Wednesday, after the commission sought advice from the state attorney general’s office and found that not enough commissioners were present for their vote to have legal standing.)

Michael Rabel, chair of the physical therapy department at the University of Maryland Eastern Shore, said data from the federal Health Resources and Services Association project there will be too many physical therapists in the state relative to jobs available even without an additional program.

“Basically, supply exceeds demand, not only nationally but in Maryland through 2030,” said Rabel, who is also programming director for the university’s physical therapy doctoral program.

He added that there’s a national shortage of physical therapy faculty members.

“If another program opens up, where would you get those faculty from rather than taking them maybe from another program?” he said.

Roger Ward, provost and executive vice president at the University of Maryland Baltimore, said there also aren’t enough clinical placements to go around, in part because other states flush with physical therapy doctoral programs, such as Pennsylvania, have students do their clinical hours in Maryland in response to their own site shortage.

Programs in these states “are competing viciously with each other, and I’m not sure that’s what we should aspire to in Maryland,” he said.

He added that both universities could easily ask their accreditor to expand the number of students they serve, if they had the faculty members and clinical sites to serve more students, but they don’t.

He noted that whatever happens, the University of Maryland Baltimore’s program will survive, but for a smaller program such as the University of Maryland Eastern Shore’s, the consequences could be more dire.

“Some institutions have the wherewithal to weather it. We will be fine,” Ward said. “But for smaller institutions, the impact is much more significant.”

A Repeating Problem

Catherine Motz, chair of the commission, said despite recent cases that have garnered public attention, objections to academic program proposals are actually relatively rare in Maryland. Out of roughly 3,700 programs proposed between 2017 and 2022, only 15 have required a review meeting.

Brian Prescott, president of the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems (NCHEMS), a higher education consulting organization, said Maryland’s review process nonetheless appears to be “somewhat more contentious” than similar processes in other states because of the lawsuit and 15 years of “calcified distrust” between institutions. However, he wouldn’t be surprised if other states become more like Maryland as demographics shift and institutions increasingly vie for a shrinking number of college-age students.

As an outgrowth of the 2006 lawsuit by HBCU advocates, a Maryland General Assembly work group is in the process of assessing the Maryland Higher Education Commission’s process for reviewing academic programs. The work group is expected to issue a report with recommendations on how to improve the process by December.

The state Legislature also requested a report from NCHEMS, released last year, regarding the commission’s review process, its possible faults and how it compares to other states that conduct similar kinds of reviews.

The report recommended the commission more clearly define terms such as “unnecessary duplication,” encourage universities to collaborate more when developing programs and clarify the different missions of different kinds of institutions in the state, among other suggestions.

“The objection process in Maryland is much more prone to being used by institutions to reduce competition amongst them,” Prescott said.

He believes competition between universities can be healthy, but he also worries that too many objections to duplicate programs might not be good for students in the long run. For example, he argued that students sometimes need the same kinds of programs offered in different areas of a state so a student living in Baltimore doesn’t have to commute to the Washington, D.C., suburbs or vice versa.

“The state had created historic inequities in the way that historically Black institutions are being treated,” he said. But by and large, “to be quite blunt about it, I think that funding them more effectively … is a better way to address that historic inequity than carving out spaces for one institution to be offering a particular program and not others.”

Ward, of the University of Maryland Baltimore, hopes in all these attempts to reform the review process, “we don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater.” He believes the commission is right to be extra sensitive to “making sure that we’re not cannibalizing each other in the state.”

Motz said eight of the 11 commissioners, including herself, were newly appointed in recent months, and they are currently focused on performing the current review process as accurately and transparently as possible. For that reason, the commission will now be including vote counts, and how each commissioner voted, in its public decision letters announcing whether new academic programs move forward.

But Motz also looks forward to an updated process and is hopeful that the forthcoming recommendations from the legislative work group will help the commission institute a process that allows for more collaboration and healthy competition between institutions but that also ensures HBCUs are succeeding and are being treated fairly.

The goal is a review process that focuses on “growing our state’s talent base and expanding our academic programs so that we can reverse the trend of students going out of state, so that we can retain and attract students to increase our competitiveness,” she said. But that process can simultaneously prioritize “honoring the decision in the HBCU lawsuit and ensuring that our HBCUs are positioned to thrive, because they are critical in meeting the needs of our students.”

.png)