You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

VectorUp/iStock/Getty Images

Perhaps more than any other group of prospective college students, veterans have been at risk of being mistreated by unscrupulous institutions. That’s partially because the federal GI Bill makes billions of dollars in aid available to hundreds of thousands of enrolled veterans (and their family members) each year, and because the funds historically have had fewer strings attached for institutions that enroll those students than do many federal student aid programs.

That is about to change. Two pieces of legislation enacted by Congress in recent years have required the agencies in each state that approve colleges for eligibility in the GI Bill program to conduct “risk-based” reviews to gauge whether the institutions leave students better off and provide a good return to taxpayers. The uptake has been slow, however, in large part because those agencies—like many bodies charged with regulating industries—don’t have enough employees or time to make informed judgments about all potential providers.

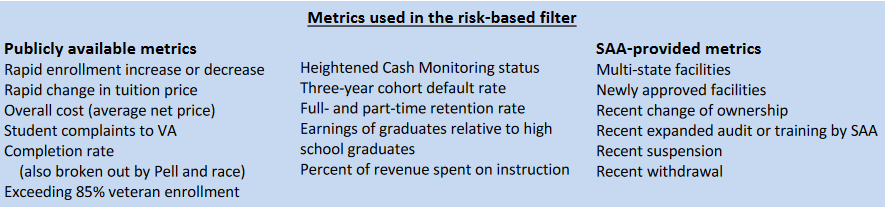

To aid their work, some nonprofit groups and the National Association of State Approving Agencies developed and tested a framework, based on publicly available data about student outcomes, complaints and institutional financial and enrollment trends (such as sharp increases or decreases in enrollment), designed to help the agencies identify the education providers that pose the most risk to veterans and taxpayers, so they can focus their scrutiny on those institutions.

The model “leverages publicly available metrics to measure the likelihood of risk posed by all institutions receiving GI Bill dollars in each state and allow [approving agencies] to prioritize limited oversight resources toward deeper review of the institutions evincing the most risk,” the American Legion and EducationCounsel, a policy and strategy firm, said in a report describing the new approach. The site visits that followed the data reviews “identified numerous risky institutional practices and outcomes, such as significant numbers of student complaints and poor institutional financial health that put students at risk of sudden college closure.”

The “risk-based” framework is noteworthy not just for its possible role in veterans’ education, but also for how it could be used by state agencies, accreditors and federal officials in identifying low-quality providers in the federal student aid programs, too.

Risk-Based Regulation

The idea that different colleges pose different degrees of risk to students (in terms of giving them bad individual outcomes) and to governments (in terms of being bad investments for the aid they provide to students) is not a new one, and most agencies, accreditors and regulators have sought to gather information about institutional performance to decide which places deserve the most scrutiny. The U.S. government, for instance, has long subjected colleges it deems to be at financial risk of closing to what it calls heightened cash monitoring, to limit their access to federal student aid funds. (A 2017 Government Accountability Office report examined how the agency identifies financially at-risk institutions.)

Numerous accrediting agencies, often encouraged by established public and private nonprofit institutions that consider themselves to be “good actors,” have experimented with “differential accreditation,” which holds colleges to different standards based on their sector, historical track record and other factors.

More recently, states such as Massachusetts—influenced by the “sudden” closure of colleges that had been troubled for some time—have explored screening tools that would identify troubled colleges whose closures could harm students. And last fall, the U.S. Education Department established an enforcement office within its Federal Student Aid unit, which it describes as taking a “risk-based approach to oversight and compliance.”

Like most of those efforts, historical efforts to guard against risk in the realm of veterans’ education have focused on financial compliance, such as whether colleges have actually distributed the aid they receive from the government to students. Legislation passed by Congress in 2017 and 2021 required the Veterans Administration and the state agencies it works with to broaden their review to whether the institutions are providing substandard educational quality, are actively misleading students or are at risk of closure, said Nathan Arnold, senior policy adviser at EducationCounsel.

But the state agencies charged with conducting these reviews have as few as one full-time employee, and they should focus their scrutiny on the programs that pose the greatest risk, Arnold said.

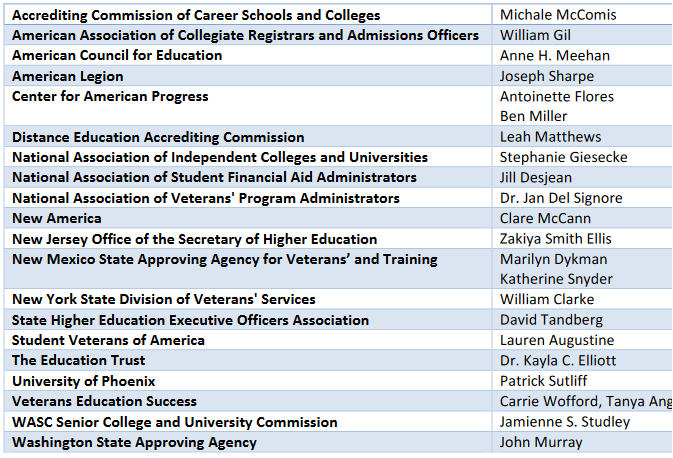

EducationCounsel convened a group of 22 experts from across the policy world (see box at bottom) to identify a set of publicly available data points that could be collected and used to separate high-risk from low-risk colleges so that state agencies can more rigorously examine—through intensified reviews of documents from the institutions, followed by site visits when necessary—the riskiest programs. (The metrics used appear at right.)

In the pilot project, Arnold said, the state approving agencies found a generally strong correlation between the institutions identified as high risk in the review process and the actual problems identified during subsequent site visits.

“Every single pilot found problems they would not have found otherwise” during their standard compliance surveys, he said. One state official quoted in the report said, “When I think about compliance surveys compared to the new risk-based process, I felt like I had blinders on that I’ve finally been able to take off.”

The 2021 GI Bill legislation requires state approving agencies to begin using risk-based approaches by this October.

Prospects in Other Contexts

Arnold and others involved in the project believe a risk-based mechanism like this one could easily be used elsewhere in higher education, and the report offers guidance to those involved, for instance, in the U.S. Education Department’s current negotiations over higher education accountability.

“In a lot of cases, these are the same schools, and the same data,” Arnold said. “We could say to a lot of states tomorrow, ‘We did this for your VA agency—we could do it for your Title IV agency.’”

Experts on higher education accountability almost unanimously agreed that differentiating by risk was a sound approach for postsecondary regulation.

Barbara Brittingham, former president of the New England Commission on Higher Education, an institutional accreditor, said many accreditors use a risk-based approach regarding finances, but they tend to favor “qualitative data” over the quantitative approach favored here.

Kristin Blagg, senior research associate at the Urban Institute’s Center on Education Data and Policy, said she believed “this type of model might be most applicable for state authorizers and accreditors, as the use of a risk filter could be a kind of data backbone for accreditors looking to set minimum standards for accreditation, or to identify schools worth additional scrutiny.”

Robert Kelchen, professor and head of the department of educational leadership and policy studies at the University of Tennessee at Knoxville, said a risk-based approach “is worth attention” but it would take some work to translate some of the criteria used to judge risk for veterans to a broader higher education context.

He also cited political issues that crop up whenever policy makers identify problems at traditional colleges and universities.

“The fundamental question here is, if data suggest a college should be closed, will policy makers follow through and allow state or federal agencies to close a college?” said Kelchen, author of the 2018 Higher Education Accountability (Johns Hopkins University Press). “Will colleges complain, scream, threaten lawsuits, if they’re put on a list of colleges requiring additional scrutiny?”

Political questions were top of mind, too, for Rebecca S. Natow, assistant professor of educational leadership and policy at Hofstra University and author of Reexamining the Federal Role in Higher Education (Teachers’ College Press).

She said via email that an accountability regimen that applied to all colleges and universities—as this one presumably would—would struggle to gain the sort of bipartisan support that measures about veterans do.

“The two main political parties have been much less likely to agree on accountability policies affecting Title IV programs more broadly, such as the gainful-employment rule,” Natow said. It could be brought about through executive action, as much federal policy making in higher education has been, but that typically results in legal challenges and flip-flopping as a new administration takes office.

Leaving matters in the states’ hands, in contrast, typically results in vastly uneven regulation, with some states being rigorous and others less so, Natow said.

But one way or another, she said, injecting a risk-based approach into higher education regulation makes sense. “The model appears to be a useful accountability tool for identifying institutions with risk factors associated with undesirable student outcomes,” Natow said.