You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

The gaps in data about the academic progress, needs and outcomes of part-time, first-generation, older and low-income college students has long frustrated higher education advocates, policy makers, charitable foundations and college administrators who want to see all students succeed.

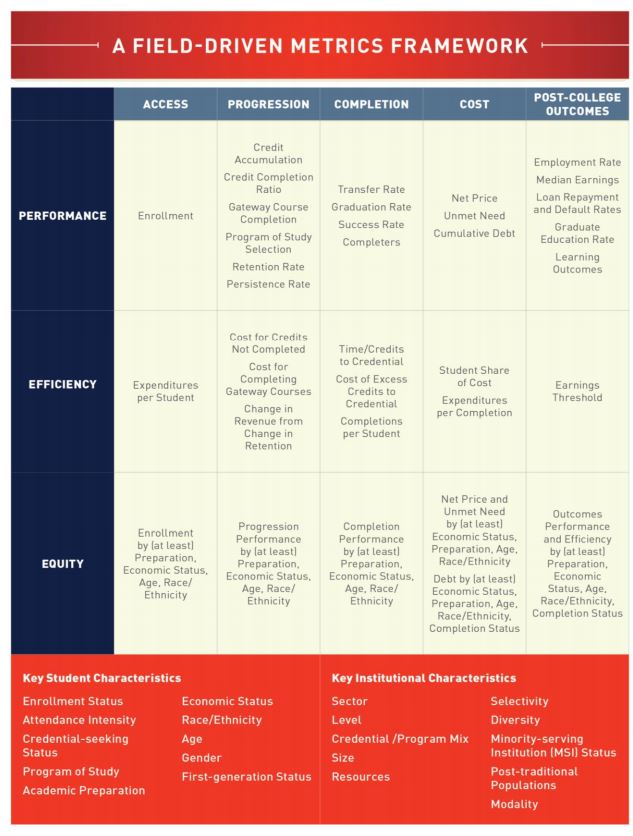

Over the last three years the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Lumina Foundation and the National Student Clearinghouse have partnered to build a system, using a new "metrics framework" developed by the Institute for Higher Education Policy, that will fill those data gaps and help institutions, states and researchers analyze the academic performance of all college students.

The partnership sidesteps the debate over, and wait for, Congress to move forward with plans to build a national student-level data system. The groups building their own system are encouraging more colleges and universities to join their partnership.

“We, as a field, have identified these general metrics that help us to understand how students are accessing, progressing and completing in higher education,” said Amanda Janice Roberson, IHEP’s assistant director of research and policy. “But between state collection and federal collection and a variety of data collection methods, we’re measuring students in different ways.”

The Postsecondary Data Partnership, which recently ended a yearlong pilot that involved three state college and university systems and 27 individual institutions, would alleviate the problem of having different and often inefficient ways of measuring students. Institutions and state higher education systems would submit data about their students to the National Student Clearinghouse. The clearinghouse, which already receives enrollment and degree completion data from more than 3,600 colleges in the country, would also receive data relevant to the partnership.

As part of the partnership, the clearinghouse validates the data and creates analytical and interactive dashboards. Those dashboards reflect the metrics that are often missing or inadequate for measuring such outcomes as students' credit accumulation, employment rates and costs for not completing credits. The Institute for College Access and Success, a progressive group that focuses on affordability and access in higher education, recently released a new report calling for the federal government, states and accreditors to standardize how they calculate job placement numbers for higher education programs.

“The core innovation is making sure the experiences of low-income students and students of color are counted,” said Jennifer Engle, deputy director of postsecondary success in the United States program at the Gates Foundation. The foundation also helped develop the framework with IHEP.

The clearinghouse sends reports on the data collected to organizations and agencies, including those already in the partnership such as Complete College America, Achieving the Dream and Jobs for the Future. These nonprofit organizations have been the leaders in promoting popular initiatives such as remediation reform and reverse transfer to increase and improve students' employment and education outcomes. Reverse transfer allows students who've already transferred from a community college to a four-year institution to earn an associate degree from the community college. Remediation reform involves getting students into credited English and math courses at a faster pace than noncredit, traditional remedial classes do, thus helping students to complete college in less time and earn degrees faster.

Groups such as Complete College America and Achieving the Dream are now also asking their member institutions to join the partnership. The clearinghouse is hoping to expand the partnership to up to 500 institutions by the end of 2019, said Doug Shapiro, executive research director of the clearinghouse.

Laurie Heacock, vice president for data, technology and analytics at Achieving the Dream, said the organization will host information sessions about the partnership during its national convention in February.

"When you have disparate data collection systems that have different cohort definitions, with some only looking at entering fall student cohort and some only looking at entering full-time students, for community colleges that is problematic,” Heacock said.

Federal data collection systems such as the U.S. Department of Education’s Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System have only recently expanded from only using first-time, full-time status to measure graduation rates. The department made changes last year that allowed completion data for part-time and non-first-time students to be collected and published.

Federal data collections do a poor job of measuring student metrics such as retention, academic momentum and credit accumulation, said Travis Reindl, a senior communications officer with the Gates Foundation. Those metrics have become commonplace in measuring student performance and their likelihood of graduating.

The data partnership hopes to address such shortcomings.

The changes can't come soon enough for John Armstrong, a senior policy analyst with the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association. During a presentation to colleges about the partnership at CCA’s national convention earlier this month, he complained about the slow pace at which federal and state agencies collect and disaggregate information across race, ethnicity, gender and other student identifiers.

Angela Bell, the associate vice chancellor of research and policy analysis for the University System of Georgia, which was part of the pilot conducted by the partnership, said being part of the partnership meant that system administrators could now get very specific data that was once unavailable and do more sophisticated data analysis that they could then measure against or compare to the data of other institutions. For example, she said, the university system could examine the progress of first-generation Pell Grant recipients who are Asian women.

The institutions are submitting student unit record data to the clearinghouse, which means “there’s nowhere to hide,” Bell said, referring to the increased level of transparency the partnership will now provide. For example, by submitting such highly specific data, university systems or colleges can create alerts when a single student accumulates more credits than they need to graduate, she said.

A bipartisan bill that would overturn the ban on a federal postsecondary student-level data system was introduced in the Senate a year ago but has not moved through Congress.

Shapiro, the clearinghouse research director, said the partnership helps colleges and universities that aren't waiting for Congress to act and want to know their students’ performance now so they can change or adjust programs and policies to improve student outcomes in a timely manner.

“What we’re building is specifically for institutions that want to opt in to create a system that better informs them of their student success,” Shapiro said. “These are institutions who can’t wait.”

_-_04.jpg?itok=quI-qMMD)