You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

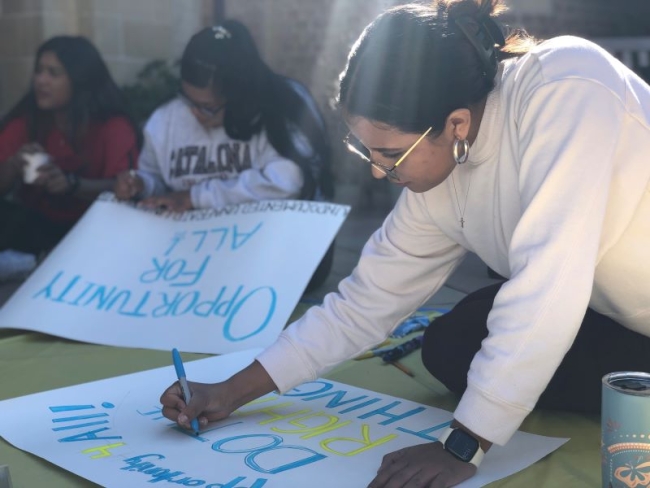

Undocumented students prepare protest signs to advocate for the opportunity to work on University of California campuses.

Hayley Burgess

Undocumented students in California, backed by prominent legal scholars, are advocating for the University of California system to allow them to work on its various campuses.

After a months-long campaign, the system’s Board of Regents is scheduled to review the students’ proposal on Thursday, EdSource reported. Hundreds of undocumented students and their advocates plan to rally in support of the proposal at the University of California, Los Angeles, today.

A 1986 federal immigration law prohibits employers from hiring undocumented immigrants. The law poses a significant financial challenge to undocumented students who also lack access to federal financial aid because of their immigration status. The nearly 100,000 undocumented students in California also receive state aid at low rates because they get little or inaccurate information about their aid options in high school and receive inadequate support navigating the application process, according to a report by the California Student Aid Commission. The Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, or DACA, an Obama-era program that protects immigrants brought to the U.S. as children from deportation, allows recipients to work in the U.S. legally, but recent court rulings currently prevent new applications to the program, resulting in a growing number of students without its protections.

A coalition of affected students, the Undocumented Student-led Network, sent a letter with the proposal to allow them to work on campuses to UC system president Dr. Michael Drake last fall. The proposal argues that states, and state entities such as state public university systems, aren’t subject to the Immigration Reform and Control Act, based on a legal analysis by the UCLA Center for Immigration Law and Policy. The center’s faculty co-directors issued a memo detailing their legal theory and signed by 29 constitutional and immigration law scholars across the country, including prominent scholars such as Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the UC Berkeley School of Law.

The scholars argue that a 1996 congressional amendment to the law specified that it applies to “an entity in any branch of the Federal Government” but notably doesn’t include states.

“There’s no question that the UC has the legal authority to do this,” said Ahilan Arulanantham, professor from practice at the UCLA School of Law and faculty co-director of the law school’s Center for Immigration Law and Policy. “It’s really a question of political will.”

“The students are admitted to UC on the promise that they can get all of the educational opportunities available to any other student, that they really are being admitted and existing within the university community on terms of full equality,” he added. “That, of course, includes the ability to work … As DACA disappears, the university is now failing to keep that promise. This proposal offers the university an opportunity though to fill that gap and ensure that it does keep that promise.”

Karely Amaya, a first-year graduate student at UCLA whose family brought her to the United States when she was 2 years old, said the UCLA Labor Center offered her a research assistant job that she couldn’t take because of her undocumented status. The job would have been an exciting professional opportunity and come with pay and tuition remuneration, which would have significantly helped her, she said.

If the Board of Regents adopted the proposal, “it would be life-changing,” she said. “It would completely change my game. I’d be able to navigate school without the anxiety of how I’m going to pay for it, how am I going to fit in, not being able to gain professional experience. When I graduate, I could potentially work for the university if they adopt this.”

She noted that there are paid fellowships available to undocumented students in the UC system, which she and others advocated for, but they’re limited and indirectly force the students to compete with each other for scant resources. There are also private or state-funded scholarships available to them, but the aid often isn’t enough, she said.

“We need to be able to afford rent,” she said. “We need to help support our families back home. We need to feed ourselves … It’s not equal. It’s not the same, and it will never be enough. We need full employment.”

A New Legal Argument

The UC system would be wading into new legal territory if the Board of Regents votes in favor of the proposal. The campuses would be operating on an interpretation of the Immigration Reform and Control Act that hasn’t been used before, Arulanantham said.

He believes no other higher ed institution or system has used this legal solution, or any other, to permit employing undocumented students. However, he highlighted the legalization of marijuana in certain states, despite a federal ban, as a parallel case.

Arulanantham and his colleagues did months of research and held listening sessions with professors and litigators, and “people had various ideas for how to refine the argument in different ways, but everybody agreed that there was no major flaw with our basic theory,” he said.

Miriam Feldblum, executive director of the Presidents’ Alliance on Higher Education and Immigration, said the proposal may be difficult for campuses to put into practice, even though the legal thinking behind it is sound.

The proposal is a “timely and valuable effort, and one that also has a lot of complexity and raises a lot of questions in terms of implementation,” she said. “Whether it has to do with an HR system or benefits or taxes, I think there are just a number of questions. What would this mean for a student who was engaged in this practice in terms of any future [immigration] status adjustment?”

She believes the details would need to be carefully ironed out, though the idea is “worth exploring” and college administrators nationwide are curious about it. The alliance held a virtual briefing about the proposal in March, and about 550 people signed up to attend. A webinar last October on “funded experiential learning opportunities,” like paid fellowships and internships for these students, attracted nearly 1,000 registrants from campuses across the country.

As more undocumented students come to college without DACA status, institutions are looking for “creative” and “alternative” ways to support them, she said. “These are students who want to develop and engage in career preparation, and what we know is that work and learning opportunities are a part of that.”

Experts say if the proposal passes, the decision is likely to be challenged in court.

Daniel Morales, George A. Butler Research Professor and associate professor of law at the University of Houston Law Center, said the legal argument is “strong,” but “there’s no way this isn’t going to be litigated. I would be so shocked if it just sat there and California did what they wanted.”

He believes the UC system should adopt the proposal regardless of potential legal challenges.

“It’s worth doing, even if California loses, because it is putting state power and the stature of the state behind the sort of values California claims to embody,” Morales said. “And that’s worth doing at a moment where there’s just absolute stagnation at a national level on this issue.”

He also noted that the state of California expends resources on undocumented students as they attend public K-12 schools and universities, but then doesn’t provide them the avenue to contribute to the workforce, which is arguably a “real economic detriment to the state of California.”

“States are investing substantial quantities of money in these students, and then they can’t reap any of the benefits of those investments,” he said. “California educated these kids all the way through.”

The Board of Regents’ decision may prompt other states to follow suit. Morales said if the University of California system is first to employ undocumented students, public higher ed systems in other blue states, such as New York or Illinois, are more likely make similar moves since they wouldn’t have to bear the brunt of court challenges alone.

Amaya is excited by the possibility of the campaign spreading.

“The UC is the third-largest employer in California,” she said. “A lot of progressive immigration policy has started in California.” Policy change comes from “people organizing, people asking … States are looking to California [for] what can we do to advance immigration reform and give rights to immigrant people.”

.png)

.jpg?itok=QW-IeiPc)