You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

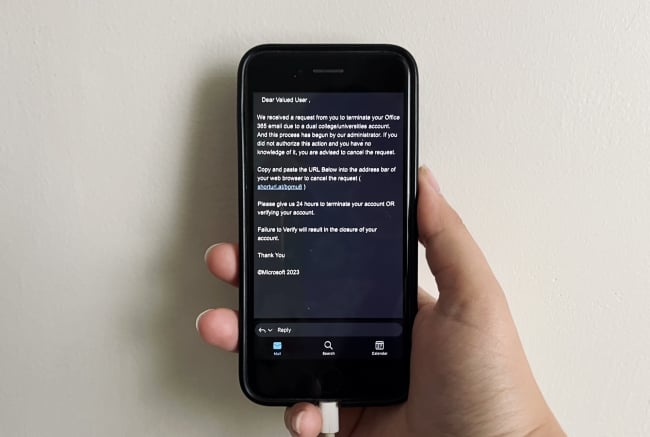

An email received by Fandrei and students at several other universities asked them to navigate to a link where they could recover their Office 365 account. The email was a phishing attempt aimed to steal the students’ credentials.

Johanna Alonso/Inside Higher Ed

When Evan Fandrei got an email that appeared to be from a fellow California State University, Long Beach, student, he didn’t bat an eye. It wasn’t until he opened the message that he began to suspect it wasn’t as innocent as he’d initially assumed.

“There were a couple things that threw me off—the way it was worded and the punctuation, spaces between commas and such. Really, really particular things,” said Fandrei, who has fallen victim to a phishing scam before, although not on his CSULB email account.

The email—with the subject line “ATTENTION NEEDED!!!”—warned that someone had begun the process of shutting down Fandrei’s Office 365 account, through which CSULB students access their university email and file-hosting service.

“We received a request from you to terminate your Office 365 email due to a dual college/universities account. And this process has begun by our administrator. If you did not authorize this action and you have no knowledge of it, you are advised to cancel the request,” it read. Fandrei had to copy and paste a URL into his web browser to verify his account, it said; if he didn’t, his account would be terminated in 24 hours.

The message had indeed come from a fellow student’s email address. But that account had already been hacked by a scammer intent on convincing other students the message was legitimate, according to Bryon Jackson, CSULB’s associate vice president of technology solutions and innovation. The hackers’ end goal was to overtake student email addresses and eventually use them to scam other students out of money.

It’s an increasingly common tactic, Jackson said—so common, in fact, that emails sent from one CSULB student to another now include a banner warning the recipient to be wary of job offers and password-reset requests, two particularly common scams.

“We’re trying to tell them, ‘Look for this content, and if you’re unsure, send it to alert,’” he said, referring to the service through which students can report suspicious messages.

Influx of Scams

Students have long been targets of so-called phishing scams, in which the perpetrator attempts to trick the victim into revealing their log-in or other private credentials by pretending to be a legitimate company or figure.

But CSULB data show that after a lull, such scams are on the rise. The number of compromised student accounts at CSULB peaked during the height of the pandemic, when students relied especially heavily on email to communicate with their classmates and professors, but they declined to almost zero after the university implemented two-factor authentication at the beginning of 2021. Two-factor authentication requires users to affirm their identity using two different types of credentials—typically both a password and a one-time security code sent to their device.

Now, phishing is on the rise again, with the number of compromised student accounts jumping from seven in the third quarter of 2022 to 82 in the second quarter of 2023. Employee accounts have not experienced a similar increase.

Cal Poly Pomona, also part of the CSU system, and Pennsylvania State University have also reported recent surges in phishing attempts.

Besides threatening to shut down email accounts, scammers also commonly offer students jobs—often with better pay and more flexibility than they could find on campus. After assigning some menial tasks, they generally send their victims fraudulent paychecks before claiming to have overpaid them and demanding the money be returned.

“New students at universities are the ones who succumb to this most often. It’s a new environment, they’re away from home, they definitely need jobs, they need money, and so they see these enticing offers that are almost too good to be true—because they are,” Jackson said.

Shomir Wilson, an assistant professor at Penn State who has studied the strategies cyber-fraudsters employ to target universities, said that these types of scams have been on the rise in recent years, possibly due to the effects COVID-19 had on the job market.

Over all, Wilson’s research found that scams that prey on university students and employees tend to be more personalized and complicated than other types of digital scams. He and his fellow researchers identified eight major types of scams that are used to target students; in addition to email account and job scams, two others that are currently popular are those that specifically target disabled students with employment opportunities and “personal request” scams, in which the sender poses as a higher-up and asks students or employees to perform tasks.

“There’s this whole little world of scamming specifically for students,” Wilson said. “Some of this stuff is perennial; some of this stuff sort of comes and goes.”

Protecting Students

It can be difficult for universities to teach students how to avoid cybercrime. Fandrei, a third-year CSULB student, said he couldn’t recall receiving any education about how to spot a fraudulent email like the one he’d received; his knowledge of the matter came from having been phished once before, and from his parents.

Jackson said the university has resources available to help students arm themselves against scams, including the “Phish Bowl,” a catalog of known phishing scams that students can compare to questionable emails they receive.

The university has also begun providing training during orientation.

If students fall victim to a scam, CSULB helps them recover hacked emails and tries to connect them with basic needs services if they’ve lost money.

Other institutions, including Penn State, have sent out alerts recently noting an increased number of scams and asking students to remain vigilant, as well as providing tips on how to avoid getting scammed.

“Some advice we generally provide is to trust your instincts. If an email seems suspicious, be wary and slow down. Read the message carefully to determine if it seems like something you would get from the sender and if it sounds authentic,” Kyle Crain, Penn State’s acting chief information security officer, wrote in an email to Inside Higher Ed. “If you click on a phishing email ‘just to check’ if it’s really from the person or organization it says, it may already be too late, as simply clicking on a link can infect your system with malicious code. Also, some signs of a phishing attempt include mismatched email domains, bad grammar and spelling, and an urgent call to action.”

Universities are also working to figure out how to catch up to the scammers, who have developed workarounds to protections like two-factor authentication by directing students to communicate with them through a nonuniversity email address or by utilizing “man-in-the-middle” cyberattacks to intercept authentication codes, Jackson said.

Sometimes, students look out for each other. When Fandrei received the phishing email claiming he needed to verify his Office 365 account, he posted it to Reddit to try to warn others.

“That component of it coming from a student email—I know someone’s going to fall for it,” he said.