You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

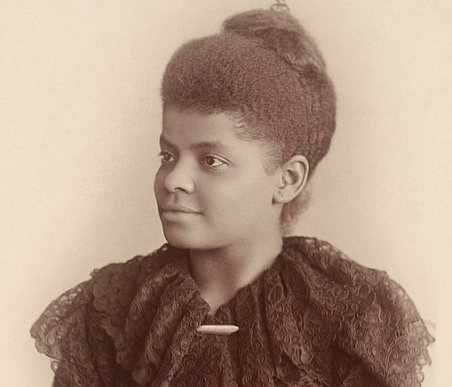

Ida B. Wells, journalist and civil rights leader.

Mary Garrity/Restored by Adam Cuerden/Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The humanities are under siege in higher education. Beyond the waning funding and influence of humanities departments and curricula, we find ourselves in a dystopian moment when book banning and legislative efforts to forbid curricula on racial and gender inequities are real threats to American education.

On the other side of the political aisle, there has been a clamoring among students and faculty for the centering of women from marginalized intellectual traditions and communities, especially Black women, in higher education. Many prestigious universities have attempted to resuscitate the flailing humanities by diversifying their core sequences. At Washington University in St. Louis, where I teach, my courses move beyond the white, male, Eurocentric canon to include a diverse collection of women, such as Ida B. Wells, Anna Julia Cooper, Simone de Beauvoir, Hannah Arendt and Iris Marion Young, among many others.

While I have been fortunate in that my students have demanded syllabi with a wider representation of voices rather than call for the elimination of critical race theory and gender studies, many bristle when they engage with women writers. “Why are we reading this?” one student asked, frustratingly, in one of my courses. “Her politics are annoying,” another student lamented. “She’s a bad feminist,” a third student protested. These are just a few of the disheartening student responses to the ideas of women that I have encountered in my classroom.

Our intellectual engagement with the ideas of women in the classroom requires us to do more than simply add them to our syllabi. It requires us to take their ideas seriously.

This past fall, one student protested about reading Hannah Arendt. Unlike Karl Marx, who traces modern oppression to capitalist exploitation, Arendt urges her reader to consider whether the human necessity of labor is oppressive. A student raised his hand, and I expected him to ask a clarifying question about the material in front of us: Why does Arendt call labor futile? How have humans attempted to transfer labor to others through systems of oppression? Yet this isn’t what he said.

“Why are we reading Arendt?”

I was floored. “Well, we are reading her, like we read all of the other figures on our syllabus, to try to understand her ideas about politics.” He didn’t bite. I had come to class prepared to guide my students through a provocative and dense piece of political philosophy, but I hadn’t anticipated having to defend my inclusion of Arendt on the syllabus.

In my African American political thought course, my students were tough on the women on our syllabus, especially Ida B. Wells. They objected that she replicates white, masculinist views of political leadership and reinforces the myth of American excellence. These are fair critiques to raise against Wells, but their tone was more antagonistic than necessary. One Black female student urged her classmates to be more patient with Wells. To bolster this student’s intervention, I reminded the class of an expectation that I set at the beginning of the course, that we can engage with figures generously, on their own terms, even if we are also critical of them. Some students were more open to Wells after these provocations, but others maintained their unsympathetic posture.

My students do not criticize these women’s better-known male counterparts for similar shortcomings. They are not deterred by Marx’s dense critique of capitalism or W. E. B. Du Bois’s elitist defense of Black education. In the mouths of Marx and Du Bois, these ideas deserve our sustained attention. Arendt and Wells are not granted the same grace but are put on unfair pedestals that no political thinker—regardless of gender—can reasonably live up to.

Students’ hostility toward women seems exacerbated by their high expectations of them and the inevitable fall from grace. Students assume that, by incorporating marginalized voices into our courses, they will engage with figures that reflect their intuitions about politics. But what they find are women with complicated ideas. They expect the dead white men to defend slavery, imperialism and capitalism, but they are dissatisfied to see Wells or Beauvoir implicated in legacies of racial oppression and economic exploitation. But what if the women that we have added to our syllabi are just as complicated as the men they have dethroned?

In my conversations with colleagues at other universities, I have learned that this challenge also plays out in different—albeit related—ways. One female colleague at a Jesuit university shared that her students are unwilling to criticize the ideas of women, especially Black women, because they confuse equal dignity with unqualified deference. Another female colleague at an Ivy League institution shared that her students try to understand the ideas of women by considering their lived experiences rather than treating them as producers of knowledge. Both approaches are different versions of the same problem that I encounter in my classroom, as students careen between hostile dismissal and blind acceptance.

What might inclusive thinking look like beyond merely adding women to our syllabi?

Here is a framework for the kind of questions that we, as professors and students, might ask when engaging with Wells, for example. How does she understand the role of Black leadership in the pursuit of racial justice? What historical constraints shape her ideas? How does her work sharpen our thinking about political resistance to racial oppression today? The crucial work of building a more inclusive humanities curriculum does not end with syllabus construction. As professors, we must empower students with the interpretive, analytical and critical skills to engage with the ideas of women writers and foster an ethos of intellectual engagement with the ideas of women in our classrooms. In turn, students should be careful not to force modern standards onto historic figures and make a concerted effort to read the women on our syllabi on the same terms as the men from the starting point of intellectual curiosity. Together, professors and students can best celebrate the ideas of women by attempting to understand them, a profoundly generous gesture.

Wells and the many other women on our syllabi are worthy of our consideration not because they are women, but because they sharpen our thinking. If we fail to afford them the intellectual respect that they deserve, we will fail the very worthy women who finally find themselves on our syllabi and the many more worthy women not yet recovered.

.png?itok=IbqmTd2P)