You have /5 articles left.

Sign up for a free account or log in.

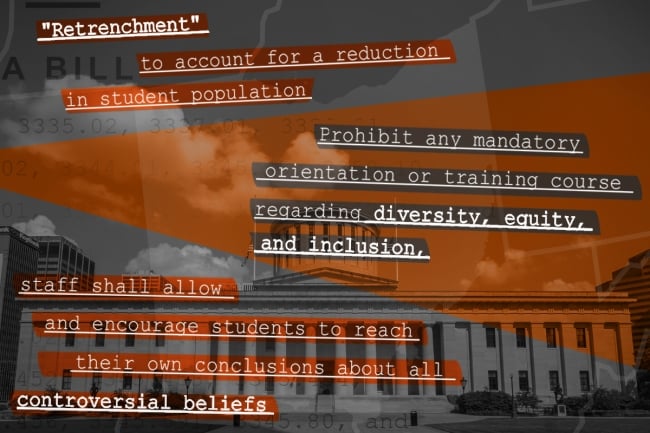

The 11th draft of Ohio’s SB 83 maintains a ban on mandatory DEI programs and introduces new retrenchment provisions.

Photo illustration by Justin Morrison/Inside Higher Ed | Photo: Creative Common | Documents: Ohio House of Representatives

Ohio lawmakers have been wrangling since March over a highly contested higher education bill that would prohibit public colleges and universities from implementing diversity, equity and inclusion programs and remove job protections for tenured faculty members and staff, among other restrictive measures.

Senate Bill 83, the Higher Education Enhancement Act, proposes a massive overhaul of the state’s public higher ed system. It bans colleges from establishing mandatory diversity, equity and inclusion programs and allows universities to fire tenured professors for a broad list of reasons, including as part of retrenchment, which under the bill does not require an institution to declare financial exigency. The bill would also create a posttenure review process and slash employees’ collective bargaining rights.

Other provisions, including a ban on faculty strikes, a requirement that all syllabi be publicly available for at least two years and that all students take a civics course, have been variously added and removed from the bill as lawmakers have heard from unhappy constituents opposed to such measures. The latest version of the bill, introduced last week, is the 11th rewrite.

Sara Kilpatrick, executive director of the Ohio Conference of the American Association of University Professors, said the latest version of the bill represents “one step forward and two steps back.”

“We were pleased to see the strike ban dropped from the bill, because that’s a fundamental collective bargaining right,” she said. “However, the very broad definition of retrenchment essentially would give carte blanche to management at our universities to shutter programs and terminate faculty positions.”

The bill is currently stalled in the House higher education committee, where it has been the subject of four hearings since May. Meanwhile, there’s been significant pushback from faculty, students and administrators who oppose the bill.

Unlike anti-DEI legislation that has gained quick support in Texas and Florida, the Ohio bill touches on a host of other topics. But despite a Republican supermajority in the state Legislature, the bill still faces roadblocks.

A Senate hearing on the bill in April lasted more than seven hours as all but three of more than 100 people who commented spoke out against it. (Some 500 people in all had signed up to speak.)

“Our goal was to try to accommodate as many objections as we could without sacrificing the core principles of the bill, certainly, which is to enhance higher education in Ohio,” State Senator Jerry Cirino, the Republican who sponsored the bill, told The Ohio Capital Journal.

The Board of Trustees at Ohio State University expressed strong opposition to the proposal in May.

“We acknowledge the issues raised by this proposal but believe there are alternative solutions that will not undermine the shared governance model of universities,” the Ohio State trustees wrote.

The presidents of the University of Cincinnati and Miami University, in Oxford, Ohio, also issued public statements that month voicing various concerns about the bill, as did the Inter-University Council of Ohio, which represents both universities and the state's 12 other public institutions. The letter to Cirino stated "serious concerns" about the legislation and cited "government overreach, increased bureaucracy, and costs of implementation," among others. (This paragraph was revised to reflect that the Miami University president's statement did not specifically oppose the bill.)

"As SB83 brings more government regulation into our universities it creates unnecessary bureaucracy, duplication of programs, and increased costs," the letter states.

State Representative Tom Young, a Republican and chair of the House higher education committee, said he is satisfied with the current version of the bill and feels “very good” about its chances of moving out of committee. He added that he’s heard “next to zero” concern about the bill from his constituents in southwestern Ohio.

“The bill has come a long way from when it was first introduced … The key points that were objectives, as far as I was concerned, were accomplished,” he said.

Both Republican and Democratic members of the committee have said they still have hesitations about the measure, however. That includes Representative Gail Pavliga, a Republican on the committee whose district includes Kent State University.

“She’s not strongly in favor of the current version, or any version that’s been put out this far,” said John Billings, Pavliga’s constituent aide. He noted that voters in her district overwhelmingly oppose the bill.

“I have had exactly zero people that have contacted me in favor of it,” he said.

Representative Joe Miller, a Democrat and ranking member of the committee, views the bill as an infringement on labor rights, free speech and faculty job security that will deter top-tier faculty from coming to Ohio.

“Why would a professor choose to work in these conditions when weighing an institute of higher education in Ohio against those in other states?” Miller wrote in an email.

“I don’t like to deal with hypotheticals, but what I do know is that it is obvious from the overwhelming amount of testimony against SB 83 in the Senate that students, faculty and colleges do not want this bill to pass,” he added.

Unpersuasive Amendments

The many changes to the bill have not changed many minds.

The most significant amendment was the removal of the prohibition on faculty strikes, which would have made them a fireable offense.

The cut was “meaningless” to faculty representatives who see the broad justifications for retrenchment as equally detrimental if not more so than a ban on strikes.

Under the new definition of retrenchment outlined in the bill, institutions can eliminate programs and/or tenured faculty positions “to account for a reduction in student population or overall funding, a change to institutional missions or programs, or other fiscal pressures or emergencies facing the institution.” Faculty with between 30 and 35 years of tenure are excluded from this mandate.

Workload, employee evaluation and tenure policies also are prohibited subjects in collective bargaining under the current version of the bill. Critics say such measures “effectively [end] meaningful tenure.”

“It is so broad that, virtually, you could use any scenario to justify retrenchment,” Kilpatrick, of the state AAUP, said. “A program conceivably could lose a single student and they could say, ‘We’re going to retrench.’”

Young said the legislation has to create a one-size-fits-all policy that leaves “enough leeway” for university leaders to decide what works best for their institutions.

“If universities are going to survive, they have to rightsize their universities to adhere to the demands of the Legislature, the governor and Jobs Ohio,” he said, referring to a state-run economic development corporation.

State Representative Mary Lightbody, a Democrat on the committee and a former college instructor, said she understands the need for some retrenchment.

“The number of students that we have coming into our colleges and universities is lowering and their interests are shifting. So you do have to have some flexibility,” Lightbody said. Still, she wonders, “Are we just giving the university administrators permission to take apart and dismantle what had been a highly popular and very significant program at the university?”

Jill Galvan, a board member of the AAUP branch at Ohio State University, the state’s flagship institution, doesn’t buy the argument that intent of the bill is to support college administrators as they cut costs.

“The state contribution to universities has just really declined, and so the idea that the state is a defender of the budget at universities, it’s just really ridiculous,” Galvan said.

Students and free speech advocates were most concerned about the anti-DEI provisions in the bill and a prohibition against institutional leaders and employees taking stances on “any controversial belief or policy”—including climate, foreign and immigration policies, electoral politics, DEI, marriage, or abortion.

Updated language now allows institutions to take stances on those subjects when the ban would affect “funding or mission of discovery, improvement, and dissemination of knowledge.” Opponents say the change is not enough.

“In order for this bill to no longer be of concern for free expression advocates, it would have to remove all references to mandated institutional neutrality, whether specific or general,” said Jeremy Young, program director for Freedom to Learn at PEN America, a free speech organization.

He characterized such mandates as “terrifying,” “counterproductive” and “draconian.”

“This is a system that is guaranteed to create absolute paralysis and absolute fear all over the campus.”

Clovis Westlund, who directs student advocacy at the grassroots organization Honesty for Ohio Education, agreed that the DEI measures are harmful.

“Senator Cirino has spoken about the idea of intellectual diversity that he believes this bill is promoting. We believe that this anti-DEI language is actually doing the opposite,” Westlund said.

Rag Ban, president of the Miami University chapter of the Ohio Student Association, is unhappy that the anti-DEI provisions are still included in the bill. “It’s a little insulting that they make these little changes to the bill and then parade it as new, when really, on the fundamental level, it’s the same bill,” Ban said. “It’s just a slap in the face to marginalized students who already faced discrimination on campuses.”

The student association has stated its “fervent commitment to combating” the bill. Students representing at least 10 colleges held a mock funeral for higher education at the statehouse in June, and most recently they held a protest during a governance symposium on Oct. 23 at which trustees from all 14 of Ohio’s public universities talked with legislators and weighed in on the bill.

Prospects Moving Forward

The House committee will hold its next public hearing on the bill on Nov. 15, after which members will decide whether to vote the bill out of committee. Opponents of the bill are hopeful that it will not pass despite Republican control of the state Legislature.

Lightbody said unless major changes are made, the bill is unlikely to get a single vote from Democrats. She also believes it may be difficult to get enough Republicans on board for it to become law.

“I hope that there are enough members in the majority who are listening to their constituents,” she said. “If they’re hearing, as I am, from their constituents about concerns … then I’ll be interested if they’re able to push this forward.”

Pranav Jani, president of the the Ohio State AAUP chapter, is doubtful about the prospects of the legislation.

“SB 83 keeps failing to inspire support from House legislators, and Senator Cirino keeps removing provisions to get it passed,” he said. “His narrative, of course, is that he’s listening and compromising, but we just know he’s not winning.”